What is PNF Stretching?

by Brad Walker | Updated October 1, 2024

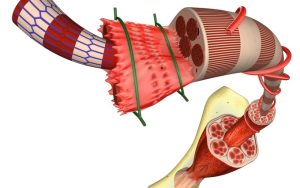

Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF) is a more advanced form of flexibility training, which involves both the stretching and contracting of the muscle group being targeted through PNF exercises. PNF stretching is one of the most effective forms of stretching for improving flexibility and increasing range of motion. Understanding what is PNF stretching is crucial for athletes and fitness enthusiasts looking to enhance their flexibility efficiently.

PNF stretching was originally developed as a form of rehabilitation, and for that purpose it is very effective. It is also excellent for targeting specific muscle groups, and as well as increasing flexibility, it also improves muscular strength.

Side note: There are many different variations of the PNF stretching principle. Sometimes it is referred to as Facilitated stretching, Contract-Relax (CR) stretching or Hold-Relax stretching. Post Isometric Relaxation (PIR) and Muscle Energy Technique (MET) are other variations of the PNF techniques. And Contract-Relax-Antagonist-Contract (CRAC) is yet another variation.

PNF Stretching: The Best for Improving ROM!

When I started using PNF stretching in the early 1990’s I quickly discovered that PNF flexibility training was a far superior form of stretching for improving flexibility and range of motion (ROM). While other forms of stretching were better when trying to achieve other goals, when it came to getting an athlete as flexible as possible; PNF exercises was the best choice.

I remember being challenged about my belief in the benefits of PNF stretching, and was asked to produce some research to back up my claims. However, back in the early 90’s the only “research” I had was the work I was doing with athletes and personal training clients, and there was very little “scientific” research about stretching in general, let alone research about PNF stretching.

Fortunately, today there is ample research to back up my claims about the benefits of PNF stretching and its effectiveness on improving flexibility and ROM. PNF training has been widely recognized for its effectiveness in enhancing flexibility, proving to be a valuable technique in both athletic performance and rehabilitation.

“Results of this study demonstrated that the increase in ROM is significantly greater after PNF stretching than after static stretching for hamstring muscles.”

“PNF stretching is positioned in the literature as the most effective stretching technique when the aim is to increase ROM, particularly in respect to short-term changes in ROM. With due consideration of the heterogeneity across the applied PNF stretching research, a summary of the findings suggests that an ‘active’ PNF stretching technique achieves the greatest gains in ROM, e.g. utilising a shortening contraction of the opposing muscle to place the target muscle on stretch, followed by a static contraction of the target muscle.”

Etnyre, B. et al. (1988) Chronic and Acute Flexibility of Men and Women Using Three Different Stretching Techniques. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, Volume 59, Issue 3, Pages 222-228

“It was concluded that the proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) techniques (i.e., CR and CRAC) were more effective than the static stretching (SS) method for increasing ROM for both hip flexion and shoulder extension for both sexes.”

PNF Precautions!

Certain precautions need to be taken when performing PNF stretches as part of PNF training, as they can put added stress on the targeted muscle group, which can increase the risk of soft tissue injury.

- During both the stretching and the contraction phase of the PNF stretches it’s not necessary to apply maximum force or intensity. In fact, PNF stretching examples work best when a gentle stretch and contraction is used. Aim for a stretch intensity and a contraction force of no more than about 5 or 6 out of 10.

- The smaller the muscle group, the less force is needed. For example, if you’re stretching the small muscles in the shoulder or neck, aim for a stretch intensity and a contraction force of about 3 or 4 out of 10.

- Also, before undertaking any form of stretching, including facilitated stretching, it is vitally important that a thorough warm-up be completed. Warming-up prior to stretching does a number of beneficial things, but primarily its purpose is to prepare the body and mind for more strenuous activity. One of the ways it achieves this is by helping to increase the body’s core temperature while also increasing the body’s muscle temperature. This is essential to ensure the maximum benefit is gained, especially when performing PNF stretching examples.

How to perform a PNF stretch?

Information differs slightly about timing recommendations for PNF techniques depending on who you are talking to. Although there are conflicting responses to the question of “how long should I contract the muscle group” and “how long should I rest for between each stretch,” I believe (through a study of research literature and personal experience) that the timing recommendations below provide the maximum benefits from PNF stretching.

The process of performing a PNF stretch involves the following.

- The muscle group to be stretched is positioned so that the muscles are stretched and under tension.

- The individual then contracts the stretched muscle group for 5 – 6 seconds while a partner, or immovable object, applies sufficient resistance to inhibit movement. Please note; the effort of contraction should be relevant to the level of conditioning and the muscle group you’re targeting (see “PNF Precautions!” above).

- The contracted muscle group is then relaxed and a controlled stretch is applied for about 20 to 30 seconds. The muscle group is then allowed 30 seconds to recover and the process is repeated 2 – 4 times.

Refer to the diagrams below for a visual example of PNF stretching.

The athlete then contracts the stretched muscle for 5 – 6 seconds and the partner must inhibit all movement. (The force of the contraction should be relevant to the condition of the muscle. For example, if you’re stretching a smaller muscle group or the muscle has been injured, do not apply a maximum contraction).

Research and References

- Adler, S. Beckers, D. Buck, M. (2000) PNF in Practice: An Illustrated Guide, 4th Edition (ISBN: 978-3642349874)

- Alter, M. (2004) Science of Flexibility, 3rd Edition (ISBN: 978-0736048989)

- Caplan, N. Rogers, R. Parr, M. Hayes, P. (2009) The Effect of Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation and Static Stretch Training on Running Mechanics. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 1175-1180.

- Cayco, C. Labro, A. Gorgon, E. (2016). Effects of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation on hamstrings flexibility in adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Physiotherapy Journal, 102(1) e190.

- Etnyre, B. Lee, E. (1988) Chronic and Acute Flexibility of Men and Women Using Three Different Stretching Techniques. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, Volume 59, Issue 3, Pages 222-228.

- Hindle, K. Whitcomb, T. Briggs, W. Hong, J. (2012) Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF): Its Mechanisms and Effects on Range of Motion and Muscular Function. Journal of Human Kinetics, 105–113.

- Lempke, L. Wilkinson, R. Murray, C. Stanek, J. (2018) The Effectiveness of PNF Versus Static Stretching on Increasing Hip-Flexion Range of Motion. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 27(3):289-294.

- Lim, W. (2018) Optimal intensity of PNF stretching: maintaining the efficacy of stretching while ensuring its safety. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 30(8): 1108–1111.

- Lucas, R. Koslow, R. (1984) Comparative Study of Static, Dynamic, and Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation Stretching Techniques on Flexibility. Perceptual and Motor Skills, Volume: 58 issue: 2, page(s): 615-618.

- McAtee, R. (2014) Facilitated Stretching, 4th Edition (ISBN: 978-1450434317)

- Sharman, MJ. Cresswell, AG. Riek, S. (2006) Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching : mechanisms and clinical implications. Sports Medicine, 36(11):929-39.

- Walker, B. (2011). The Anatomy of Stretching, 2nd Edition (ISBN: 978-1583943717)

- Yutetsu, M. Hisashi, N. Yuji, O. Shizuo, K. Junichiro, A. (2013) Effects of Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation Stretching and Static Stretching on Maximal Voluntary Contraction. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, Volume 27 – Issue 1 – p 195–201.

Disclaimer: The health and fitness information presented on this website is intended as an educational resource and is not intended as a substitute for proper medical advice. Please consult your physician or physical therapist before performing any of the exercises described on this website, particularly if you are pregnant, elderly or have any chronic or recurring muscle or joint pain.